I’ve spent most of my working life - as a BBC production person - in rooms where respectability is quietly policed. Where the tone of your voice, the school you didn’t go to, or the shoes you’re wearing tell a story before you’ve said a word. And where people don’t always know they’re judging you, because it’s all unspoken. A shared understanding of who belongs.

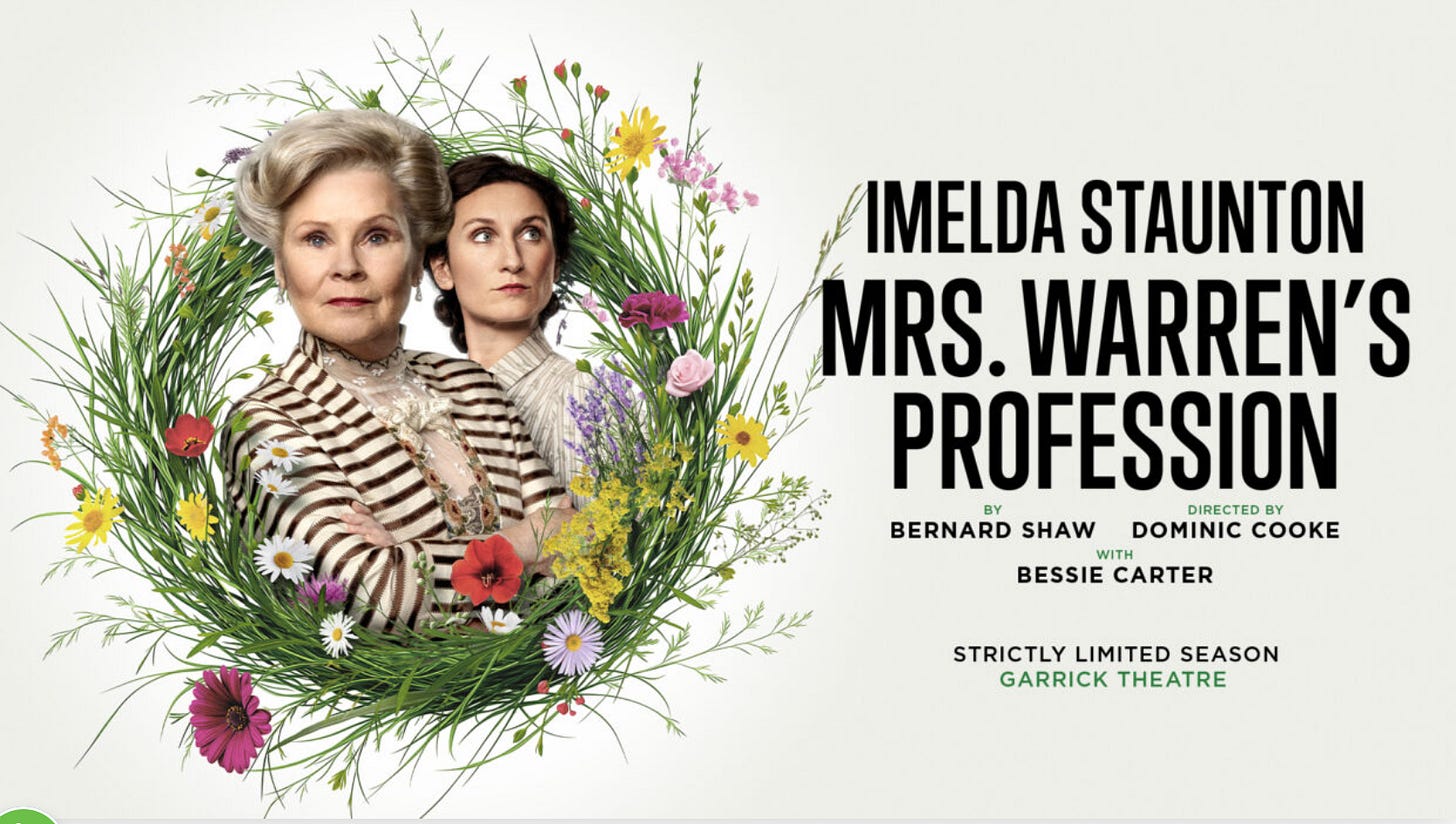

Last week, I sat in the Garrick Theatre in London and watched a mother and daughter — the brilliant Imelda Staunton and Bessie Carter — perform Mrs Warren’s Profession, George Bernard Shaw’s once-banned play about a clever young woman discovering the real source of her privilege. It’s a powerful piece of work, first staged in 1902, and still razor sharp on money, gender, hypocrisy and the social choreography we all pretend not to notice.

The premise is simple, devastating: Vivie Warren, a recent Cambridge graduate, discovers that her comfortable upbringing has been funded by her mother’s success as a brothel madam. Her mother — Mrs Kitty Warren — has built an empire based on men’s pleasure. Clean linen, European clients, good returns. “I’ve done better than most who started where I did,” she says. “I’ve turned it into a business.” But for Vivie, who doesn’t really know her mother and has been raised to believe in rationalism, respectability and hard work, the truth cuts deeper than she expects. Because the realisation isn’t just about where the money came from — it’s about what that money allowed her to forget. Or not know. Or never question.

Imelda Staunton is spellbinding. Her Mrs Warren is proud, defensive, desperate to be understood. Not for what she’s done, but for what she’s survived. Bessie Carter plays Vivie with hard intelligence, a young woman determined to live on her own terms — but not as naïve as she first appears. The real-life mother-daughter connection crackles. What could easily be a Victorian melodrama becomes a raw, painful unpicking of generational betrayal, ambition, and shame. It stayed with me long after I left the theatre.

Because the questions it asks are the same ones I’ve seen ripple through London bsed media pitching meetings, business away-days, networking events and social gatherings.

What does it really take to get ahead? Who gets to decide what’s respectable — and what’s shameful? And are you ever really accepted, if you don’t have the codes that money can quietly buy?

That’s the tension that hums through this production. Mrs Warren hasn’t just bought comfort. She’s bought access for her daughter. Education. Respectability. All the invisible tools of social mobility that middle-class life insists are earned — but are so often inherited, or acquired through the sacrifices someone else made.

And her daughter, Vivie, has no idea what it cost. She’s so busy building a life that looks “modern” and “principled” that she doesn’t see how dependent it is on what she’s been protected from.

That’s the kicker. And that’s what makes the play feel as modern as ever.

Because we still live in a world that pretends meritocracy is real. That ambition is enough. That the best ideas always rise to the top. But anyone who has come from outside the club — of class, of money, of tradition — knows otherwise.

I’ve felt it in meetings where I’ve been mistaken for someone more junior. In moments where my accent has been noted before my point. In conversations where I’ve sensed I’ve said the wrong thing, worn the wrong thing, or asked the question that wasn’t supposed to be asked. Tumbleweed moments.

You learn quickly. Not to mind too much. To speak a little slower, modulate your accent. To blend. But you also start to understand how respectability works. That it’s not about goodness or honesty. It’s about how closely you align with the codes that those “in the know” recognise.

And those codes — in Shaw’s play and in today’s leadership cultures — are often set by people who’ve never had to count the cost.

Vivie doesn’t want her mother’s money once she learns where it came from. She wants to make her own way. But Shaw is no romantic. The choice she makes — to walk away from both financial support and emotional connection — is framed not as heroic but as harsh and judgemental.

There’s no happy ending. No reconciliation. Just a woman choosing clarity over comfort. Choosing to be clean. But also, alone.

And it made me think: in a world still built on networks, favours and inherited advantage, how often do we force people to choose between inclusion and integrity?

In business, we talk about “bringing your whole self to work”. But that’s easier if your whole self fits the image of success we already understand. If you’re too different, too bold, too uncomfortable — you get quietly edged out, or endlessly asked to explain yourself.

We ask people to be authentic, but only within the lines already drawn up and which they need to work out for themselves.

Mrs Warren’s Profession exposes the lines. Then dares to cross them.

Staunton’s performance is the anchor — full of rage, hurt, and a defiant kind of pride. You may not agree with her choices, but you can’t dismiss her. And Carter plays Vivie not as a modern heroine, but as someone who learns that being principled has a cost — and that being better educated doesn’t mean being wiser.

And that, in the end, is the genius of the play. Shaw doesn’t tell us who to side with. He just shows us what it looks like when power, money, and morality get tangled — and leaves us to sit with the discomfort.

I left thinking about my own career to date. The moments when I’ve chosen diplomacy over honesty. When I’ve smiled through something I should have challenged. When I’ve seen others play the game better, because they grew up knowing the rules.

But I also left with a sense of resolve. Because while we can’t undo the structures overnight, we can at least stop pretending they don’t exist.

We talk a lot about merit. About hard work and personal grit. But reputation, more often than not, is carefully staged. Respectability can be little more than branding — a polished veneer that reassures the right people. Some of the most “successful” people I’ve worked with weren’t the brightest or the bravest. They just had the freedom to fail, knowing the safety net would hold. One former colleague springs to mind — armed with the best education money could buy, fast-tracked from the start, and blissfully unaware of the invisible scaffolding beneath them. They genuinely believe they have earned every rung. But privilege dressed up as morality, especially when it nudges others out of the way, is hard to watch — and harder to stomach.

Mrs Warren’s Profession is more than a play. It’s a mirror. Not just for women navigating ambition and compromise, but for anyone who’s ever felt like they didn’t quite belong, or had to hide the truth about where they came from to get where they wanted to go.

It asks: how far will you go to be accepted? And what’s the price of walking away?

It doesn’t offer easy answers. But it does offer clarity.

And for that — and for two breathtaking performances from Staunton and Carter — I’m grateful.

If you’re in London, do go see it. If you’re in leadership, read the play. And if you’ve ever wondered whether you’ve really been seen — not just tolerated — maybe this is the story you need to explore.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.